The History of the Hoyt Family & How Purity Spring Resort Came to Be

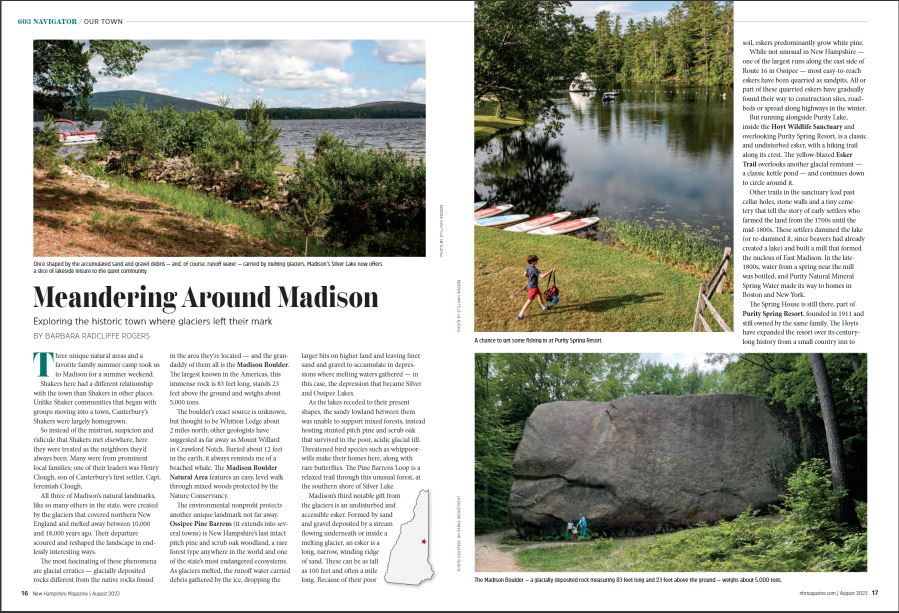

Created long ago by retreating glaciers carving into earth, the depths of Purity Lake hold many memories. Set serenely within a little valley, and surrounded by towering forests of pine, the lake has witnessed the ongoing struggles and triumphs of man. For early travelers visiting its shores, for farmers scraping existence from its land, for entrepreneurs marketing its resources and for vacationers recreating in its waters, the lake has held powerful appeal. Today, Purity Lake reflects the purest beauty of New Hampshire and a storied history as well.

Settlers in the 1700s

For the earliest pioneers, the hills and woodlands surrounding the lake held both natural beauty and a harsh reality. With steadfast determination, they cleared the land and built their homesteads. And by the turn of the 19th century, a small community, struggling to sustain itself, called Purity Lake home. To build their homes, the settlers needed the ability to turn trees into lumber—in other words, they needed a mill. For this, they looked to the expertise of the beavers. As the original residents of the valley, the beavers created their homes by building a dam at the southern end of the lake, blocking the natural flow of water. The settler recognized that it was a brilliant location. And in the late 1700s, they followed the beavers’ lead, using enormous hand-hewn timbers to construct their mill on the south end of the lake. The beaver dam was replaced with a man-made one, and two water wheels were installed to provide power for the mill.

Early records indicate that the mill and six acres of surrounding land were purchased in 1802 by the Blaisdell family for $600. Two years later, using timbers hewn at the mill, they built a salt-box style home across the street and called it the Blaisdell House, which later became the Millbrook Lodge. Living on the property, they could oversee operation of the mill—which in addition to cutting logs eventually ground corn, pressed cider and made shingles. Two of the stone grinding wheels, imported from England, still sit outside of the mill today. By 1804, the mill had become a bustling center of activity, around which grew the small village of East Madison. A blacksmith and a cooper set up shops. A general store opened. A small country school was built. And, eventually, a post office serviced the growing number of homes.

Catching the Eye and Capturing the Heart of an Entrepreneurial-Minded Couple

When the neighboring town of Madison officially became established in 1852, it was Nicholas Blaisdell who managed daily operations of the mill. An attorney from Brooklyn, N.Y., Nicholas and his wife, Martha Hood, had decided to forgo city life and return to the place of his birth. They moved into his family’s house by the lake and took charge of what was then called the Blaisdell Mill. Some years later, Martha’s sister, Mercy Hood, accompanied by her husband, Edward Eaton Hoyt—a very successful auctioneer—journeyed from New York City for a visit. They found the allure of the valley so compelling that the “Hoyt” name would ultimately be forever immersed in the waters of Purity Lake.

Edward purchased a nearby farmhouse called the Betsy Harmon Homestead. It was large enough to vacation with family and friends and to entertain his many clients. Edward and Mercy had four children, and while the entire family grew attached to the valley, one son, Edward Hoyt Jr., truly fell in love with it. Debilitated by polio as a young boy, that Edward Jr. and his family came to appreciate he may enjoy a healthier life on the lake’s shore—with its clean, fresh mountain air. And in the 1870s, they decided to let him remain in the valley in the care of his Aunt Martha. When Nicholas Blaisdell passed away in 1883, Edward Jr. helped his aunt oversee the continued operation of the mill. Since his son resided in the valley, Edward Sr. made frequent trips from the city. And during those trips, Edward Sr. began seeing the valley and its resources through an entrepreneurial eye.

Tranquility in a Bottle

Edward Sr.’s attention was drawn to a natural spring near the mill—a pure vein of crystal clear water bubbling out of the ground. Knowing that most of his fellow New Yorkers were resigned to consuming foul-tasting water, Edward Sr. saw an opportunity, and he began bottling ‘Purity Natural Mineral Spring Water.’ With the arrival of nearby rail service to the Silver Lake Depot in 1871, the bottled water could be transported by oxcart to the station, where it could then be shipped throughout New York City. In the early 1890s, Purity Spring Water, which had a reputation for containing quite amazing medicinal value, won accolades in both Boston and New York City. A 5-gallon jug cost $2.25 including shipping. In 1893, Edward registered the trademark ‘Purity’ with the U.S. Patent Office. Unfortunately, by 1900, increasing shipping costs and breakage loss caused the cessation of the ‘Purity Spring Bottling Company.’

Betting the Farm on a Better Life

In the years following the Civil War, many rural families, frustrated with sustenance living, packed up and migrated out of the area. One such family went by the name of Durgin. They were farmers who built a small number of homes along what is now the Sunset Beach Road. The Durgin family cleared trees from the land and piled rocks into walls to contain livestock. For several generations they worked the poor, sandy soil until finally deciding to depart the valley in search of better fortune. Today, you can still see the signs of their toil: stone walls that meander through the forest, cellar holes that were dug into the earth and a family cemetery that rests on a hill near the waters of Purity Lake.

As people left their lakeshore homesteads, Edward Sr. bought up the property. Eventually, he owned much of the land around the lake, and he called it Purity Spring Farms. Edward Sr.’s holdings consisted of a collection of farms, the old Blaisdell Mill and the bottling company. When Edward Sr. died in 1903, it was Edward Jr. who inherited the valley lands and committed to living out his life on the property. He married Gertrude Keith, a local schoolteacher, in 1905, and the couple moved into a cottage (which later burned to the ground) across the street from the Blaisdell House. They had two children: Ellen Mercy Hoyt (born 1907) and Edward Milton “Milt” Hoyt (born 1911). They moved their growing family into another beautiful old farmhouse across the road from the mill—which, today, is known as The Inn.

The Hoyts Become Hosts

With little money to speak of, the Hoyts began taking carriage guests into their home to supplement their income and help pay property taxes. Early guests stayed in platform tents right on the shore of the lake. Later, guests were housed in screened bungalows and cottages nearby. Edward Jr. managed the land and the operation of the mill, and he offered scenic carriage tours of the countryside for visitors. Meanwhile, Gertrude managed what the couple called the Purity Spring Mountain Inn. Early marketing efforts highlighted the peace and quiet of country life and presented the inn as a “refuge for the weary.” The Hoyts offered many activities, including swimming, hiking, croquet, archery, dances and marshmallow roasts. The inn flourished under Edward Jr. and Gertrude’s care, and Ellen and Milt met many visitors throughout their childhood years.

A Great Deal of Effort to Survive The Great Depression

But times grew tough as Milt graduated from high school in 1929. His mother, Gertrude, succumbed to diabetes, leaving the care of his aging father—and the upkeep of the inn—in Milt and Ellen’s hands. That same year, the stock market crash heralded the beginning of the Great Depression. Business at the inn was down, and the only income hewn came from the Blaisdell Mill. The family was land-poor, yet throughout the lean years, Edward Jr. refused many offers to purchase his land. He was determined to keep Purity Spring in the family and maintain it as one of the last undeveloped lakes in New Hampshire. The lack of financial stability and the passing of his mother put Milt’s desire to attend college on hold. Instead, he labored his father’s land, worked at the mill and helped welcome guests who came to stay at the inn.

The Summer Camp That Started it All

Milt’s fortune would change dramatically during the summer of 1932 with the arrival of Maud Hersey. Mrs. Hersey rented a large bungalow at Purity Spring Mountain Inn for herself and a group of six students from the Moses Brown School in Rhode Island. Nestled up in the woods behind the Blaisdell Mill, the bungalow had a large open room with a stone fireplace, a kitchen facility and a wrap-around screened porch. The boys bunked on the porch, protected from the weather, yet able to enjoy the summer breeze and sounds of the lake. Milt got along well with Mrs. Hersey and helped run the outdoor program she had planned for the boys that summer. In turn, Mrs. Hersey set out to help Milt realize his educational goals. Their union would change the course of Milt’s life—and send ripples across the course of life on Purity Lake.

From Camp to College and Back Again

Mrs. Hersey arranged for Milt to work at Moses Brown during the school year, where he gained a year of postgraduate education. His efforts earned him acceptance at Brown University, where he received a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering and a master’s in education. But his summers were still devoted to the valley. In 1933 and 1934, Milt continued to run the camp program for select boys from Moses Brown, and the experience inspired Milt to dream of one day opening a summer camp for boys. Realizing he needed help, Milt shared his vision with John Hanson, a fellow student from Brown University. In May 1935, these two men drew up plans to expand upon what had been initiated in 1932 and formalize a private camp for boys.

The Purity Spring Camp for Boys opened on June 26th, 1935. But that August, its name was changed to Tohkomeupog, an approximation of the Natives’ word for “spring water.” Eleven boys experienced camp that summer, most staying for nine or 10 weeks, at a cost of up to $150. The camp was re-located up to the Betsy Harmon Homestead, where the old farmhouse served as a dining room and lodge. A large hay-filled barn with horse stalls was modified to serve as the boys’ facilities. And a screened cabin, named Washington, was erected to serve as the camp’s sleeping quarters. Milt and John ran the camp as co-directors until 1939, when it reached about 25 campers. Then, they began recruiting fellow Brown students as staff, and Milt took sole ownership of Tohkomeupog.

Girls Gain Their Own Grounds at Purity Lake

In 1934, Milt’s sister, Ellen, established the foundation of a camp for girls at the Purity Spring Mountain Inn. When Milt moved the boys’ camp up to the Harmon Homestead, Ellen took over the bungalow behind the mill. This became the main lodge for the girls’ camp she called Wampineauk, an approximation of the Natives’ word for “pure water.” Cabins were built around the bungalow, along with other facilities, including a horse barn and riding arena. A large farmhouse, located down the main road from the mill, was used to house the older campers. Senior House, as it was then called, still exists today, but it is no longer a part of the grounds of Purity Spring. Girls at Wampineauk enjoyed similar outdoor opportunities to the boys at Tohkomeupog. And they learned a lot about the environment, as Ellen, who later became a biology teacher, specialized in nature studies. Though she did not reside full-time in the valley, Ellen returned every summer to run the camp, enabling hundreds of girls to enjoy the waters of Purity Lake.

Taking a Stab at Snowsports

During his years at Brown, Milt brought carloads of people to East Madison to spend weekends in the winter enjoying the relatively new sport of skiing. In 1938, he cleared some trees from a hill near the inn and constructed a rope tow. Powered by a Ford Model A engine, this rope tow would be the first of several lifts to transport skiers to the higher reaches of the valley. In 1939, Milt established overnight ski camps for boys and girls during school vacation weeks. In leather boots on wooden skis, hundreds of people swooshed down the tiny hills around the lake. As the popularity of skiing increased, it would transform winter operations at the Inn, revealing year-round business possibilities. But the time was not quite right. Upon graduation, Milt took a teaching position in West Hartford, CT and spend his weekends and summers in the valley.

World War II in the White Mountains

Summers during World War II were memorable for many of campers. With gas in low supply, hiking trips out of camp became even more adventurous. Tohkomeupog became a bicycle camp where campers pedaled themselves around the White Mountains. Food was carefully distributed and allocated based on the ration stamps the campers brought with them. From 1942 to 1945, as part of a national mandate, many of the sporting fields were turned into “Victory Gardens.” Wax beans were grown to support the troops overseas. And morning activities were dedicated to hoeing during the early part of the summer and picking beans in August. Boys were compensated at three cents per pound. The camp proudly held a record harvest of eight tons that was transported to Fryeburg, ME in 1945.

Finding Love on the Lake

At Wampineauk, Ellen hired Frances Hayden, a young woman from Portland, Maine, to be a counselor at the camp. When Frances met Milt, the two fell in love, and they eventually married. Milt and Fran had five children, and the first two were born while the family was living in Connecticut, where Milt was still teaching. In 1944, he decided to retire from teaching and commit to developing the year-round business in the valley. His family moved into the old Blaisdell House, and when his father, Edward Jr., died in 1952, the valley lands were passed into the care of Milt and Ellen. Milt loved the valley as much as his father. Over the next two decades, the business would experience tremendous growth. Milt and Fran shaped and shifted the property, creating much of what we know as Purity Spring Resort today. And their children were lucky enough to be the fourth generation of Hoyts to enjoy the pristine waters of Purity Lake.

New Crazes Led to New Opportunities

Adventure at the camps in the 1950s and early 1960s was highlighted by the Western Tour, a 7-week exploration that took older boys and girls to some of the most spectacular National Parks. During the summer, campers enjoyed taking part in the newest recreation craze: waterskiing. Wind-rippled smiles soared back and forth across Purity Lake. Meanwhile, tennis courts and sporting fields popped up on the property alongside a few beaches. Throughout the winters, a growing number of guests came to ski the mountain’s slopes and stay overnight in the lodge.

Having spent their summers at camp and their winters learning to ski, the Hoyt children shared their parents’ love of and commitment to the valley. Milt and Fran worked hard, desiring to expand the business such that it would always support the aspirations of their children. And they formally opened King Pine Ski Area with three trails in 1962. Purity Spring Resort incorporated in 1967.

The Royal Roots of King Pine

King Pine got its name from two very large pine trees on the property that bore the mark of King George—indicating that, before the American Revolution, they were identified and marked by British forces to be used as ship masts for King George’s Royal Navy. The trees both fell during severe storms, but today, sections of board can still be found on display in both the ski lodge and The Mill. About 10,000 skiers enjoyed the slopes of King Pine during its first season. An all-day adult ticket cost $4.00, while a single ride could be purchased for $0.50. Initially, just one double chairlift carried skiers to the top of the mountain. But a few years later, a J-bar was added to service a beginner-friendly slope. Then, in 1965, Milt subdivided a portion of the land on the mountain to be sold as house lots—an initiative devised to raise capital for expansion to the back side of the mountain, where a second double chairlift was added in 1968. Many of Milt’s old camp friends bought lots in the newly formed King Pine Area Association (KPAA), where a small community pond was available for picnicking and pathways enabled direct access to the slopes of King Pine.

Not the Kind of Campfire the Hoyt’s Were Expecting

The 1970s brought notable transition at the camps. The Camp Lodge—built from the old Harmon Homestead—burned to the ground in December 1975. Although the building was lost, quick reaction by staff saved most of the historic camp photos that had adorned the walls. The new Camp Lodge, now called Tecumseh, was completed for the summer of 1976. That summer also marked the retirement of Milt Hoyt as director of Tohkomeupog. In a midsummer ceremony, directorship was passed temporarily to Milt’s son, Robert. The following year, 1977, Milt’s eldest son, Edward H. Hoyt, commonly known as “Teddy,” became the director of the camp. While the boy’s camp was growing stronger, the life of Wampineauk was winding down. Ellen retired as director of camp in 1977, and Wampineauk ceased its operations. Today, the camp solely exists in the memories and hearts of its alumni.

Camp Gains & Family Losses

Tohkomeupog flourished under Teddy’s guidance, adding white-water canoeing to its adventure program, and celebrating a 50-year anniversary in 1981. In 1987, King Pine Ski Area celebrated its 25th anniversary with an expanded base lodge, snowmaking, night-skiing, a new triple chair lift called Polar Bear and a celebration with Governor John Sununu. A few years later, the Tohko Dome was built, featuring a climbing wall and basketball court for camp in the summer, and a skating rink for winter guests. Business was very good, and the Hoyt family enjoyed success in their little valley. Then—without warning—tragedy struck. While crossing the street on a snowmobile on January 13th, 1988, Milt Hoyt was hit and killed by a dump truck. His memorial service brought hundreds of old camp friends back to East Madison to remember the times they had here. A granite bench was erected in Milt’s honor at Sunset Beach, where one can sit peacefully beneath the pines and gaze upon the waters of Purity Lake.

One year later, 1989, Milt’s sister, Ellen, also passed away, bringing closure to the third generation of Hoyt legacy in the valley. In her will, Ellen designated about 160 acres of land—including that which was Wampineauk—to be protected by New Hampshire Audubon and to be named the Gertrude Keith Hoyt & Edward Eaton Hoyt Jr. Wildlife Sanctuary in memory of her parents. A granite bench was erected in Ellen’s honor on a ridge near the water’s edge – a favorite spot where she once delivered vesper services to the girls at camp. Although the original old bungalow and other visible Wampineauk facilities are now gone, life within the sanctuary is abundant. Floating bogs play host to rare species of carnivorous plants. Moose and deer come to quench their thirst, loon and heron nest in the reeds and turtles sun themselves on toppled logs. Here, you can sometimes hear the slapping at the water by a beaver’s tale—perhaps one of the descendants of the valley’s original flooders.

A New Mill & a New Generation

In 1992, the old Blaisdell Mill was torn down after decades of idle decay. In its place a beautiful indoor pool and fitness facility was built and named The Mill. Respecting the memory of its former life, The Mill remains a bustling center of activity for the community.

In 1996, Kathy Hoyt Morong, a member of the fourth generation of Hoyts, died after a long struggle with breast cancer. Her surviving siblings—Ted, Laura, Robert and Susan—all continued the family tradition by full-time in the valley. Ted’s eldest son, Steven, and Laura’s eldest son, Andrew, came to work at the resort, becoming the fifth generation of Hoyts to reflect upon the waters for Purity Lake.

Ted successfully directed Tohkomeupog through the turn of the century, keeping the program exciting by adding a high ropes course and mountain biking trails. Meanwhile, cross-country skiing and snowboarding were fast becoming more popular as winter sports. A new triple chairlift, called Powder Bear, was added on the front side of the mountain. And in 1998, tubing became the newest craze to hit the King Pine slopes as well.

New Grounds in the New Millennium

In July of 2000, the Hoyt family purchased 400 acres of land in nearby Freedom, NH. They acquired much of the land around Huckins Pond and the Shawtown Campground. Shawtown was developed by Dick and Nancy Pascoe in the early 1960s, who had welcomed campers for almost 25 years before retiring and selling the campground property. In the years since their departure, the property had fallen into disrepair. The Hoyts began the huge task of rebuilding with a goal of revitalizing the once thriving campground and creating one of New England’s finest RV camping resorts. Construction on Danforth Bay Camping & RV Resort took a full year. Although located on a distinct piece of land several miles south of Purity Springs, there’s a small brook that runs from the dam behind The Mill and flows into directly into Danforth Bay’s Huckins Pond, connecting both properties with the waters of Purity Lake.

Home-Grown Campgrounds

Ted Hoyt retired from Tohkomeupog on May 4th, 2001—his 60th birthday. In the company of more than 300 alumni and friends, directorship of camp passed to his nephew Andrew Hoyt Mahoney. Later that same month, the first set of campers were welcomed to Danforth Bay Camping Resort. The campground proved so successful that it quickly expanded, and in 2006, The Bluffs, a 50+ RV resort, opened for its first summer season. Now sporting more than 500 completed sites, Danforth Bay is one of the largest RV camping resorts in Northern New England. Also in 2006, King Pine replaced its old double chairlift on the back side of the mountain with a triple called Black Bear. The resort christened its newest slope Pine Brulé.

Danforth Bay commemorated its 10th anniversary during the summer of 2010. There was much to celebrate, yet the first decade of the new millennium proved bittersweet for family and friends of the valley. Frances Hayden Hoyt passed away in 2004. Remembered fondly as ‘The Lady of the Valley,’ she was a remarkable woman who helped fashion the company during its formative years. Then, in 2008, Laura Hoyt Mahoney, eldest daughter of Milt and Fran, died after a courageous confrontation with pancreatic cancer. As hostess at The Inn, Laura was well known by guests, providing them with a genuine connection to the Hoyt family. Her passing left a rift valley, difficult to fill. It also inspired the creation of the Laura Foundation for Autism and Epilepsy, a charitable organization reaching out to families living with autism and/or seizure disorders. Laura knew first-hand how devastating these two disorders were for afflicted individuals—her own grandson was among them. Spearheaded by her children, the foundation is currently striving to formalize a center of adaptive sports and recreation right here in East Madison, an effort they know Laura would wholeheartedly support.

Celebrating 100 Years

2011 was a significant year for Purity Spring. Camp Tohkomeupog celebrated its 80th birthday. Now with 20 cabins, the camp hosts more than 150 boys every season, including some fourth-generation campers. When snow fell that winter, King Pine Ski Area opened for its 50th season and welcomed about 65,000 skiers. Most significantly, Purity Spring Resort celebrated 100 years of hospitality and family tradition.

Much has transpired since those first carriage guests arrived in the valley to tent on the shores of the lake. Initially, the business of hospitality was a matter of survival. But over more than 100 years, it evolved into a strategy for success. The impact the Hoyt family has had is visible all over the valley and the resilience of the resort can be felt here too. In 2021, Purity Spring Resort joined the Highway West Vacations family, and a new chapter of Purity Lake’s story began. Whether it’s your first time visiting Purity Spring or your 50th, we look forward to offering you some warm hospitality—and a little bit of history too.

Categories

- Did You Know? 3

- Local Flavor 2

- Press 8

- Uncategorized 1